Status Update #6: All Roads Lead Back to Paris

Signing CryptoPunks Books, Curating Body Anxiety in the Age of AI, and Following the Debate About the AI Auction at Christie's

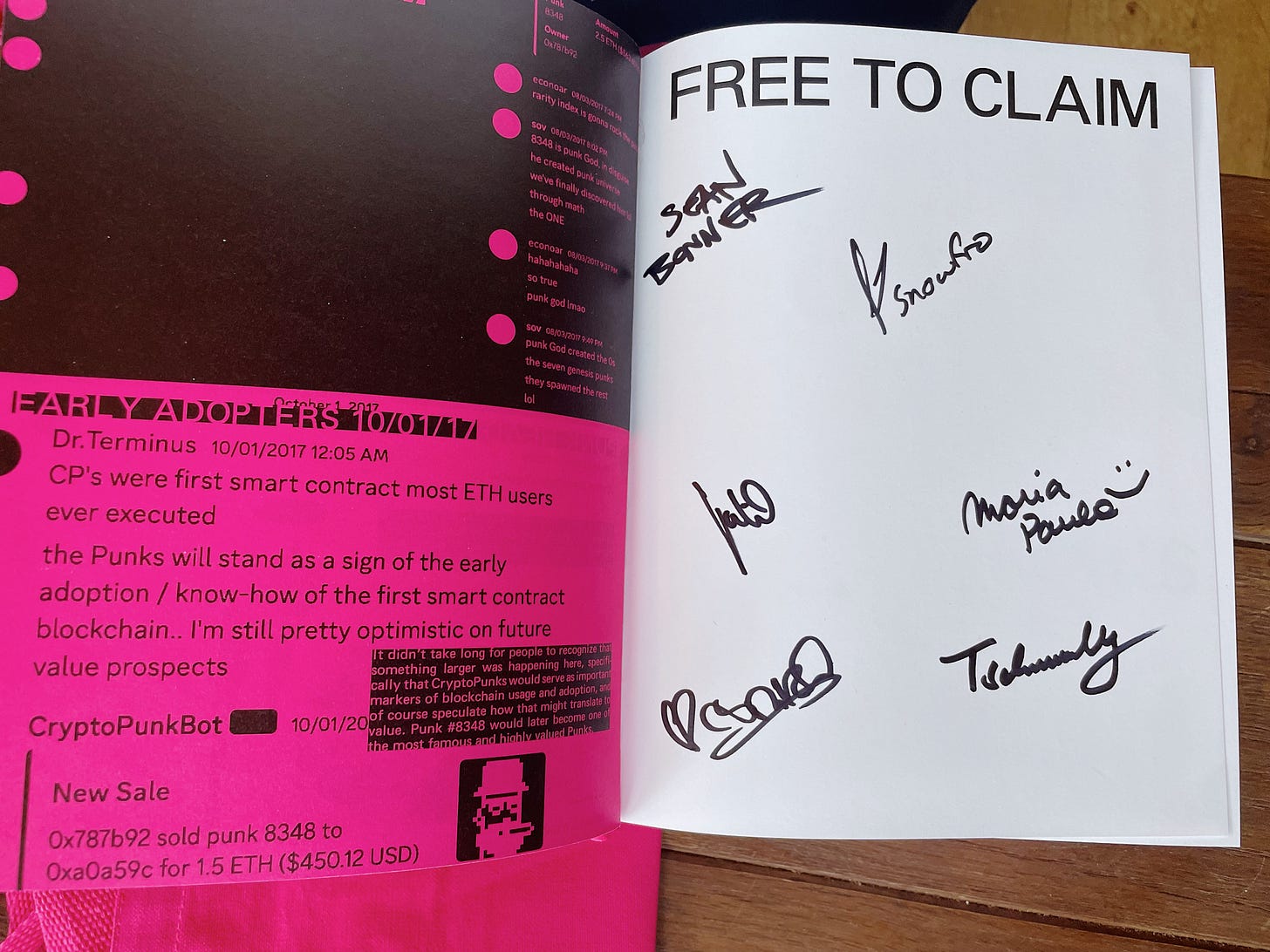

A few days ago, I realized that it's not so easy to write your own name repeatedly. Especially not when many people are watching. Suddenly, the letters didn't want to appear on the paper in the right order. So there I was, sitting between Erick Calderon (aka Snowfro), the founder of Art Blocks, and María Paula Fernández, co-founder at JPG, at the CryptoPunks Book Signing, trying hard to sign my name legibly, as both of them had readable signatures. We were joined at the long wooden table on the upper floor of the Ora Farmhouse in Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in Paris by other authors of the book.

(You can get a copy of the book here.) It felt like every few minutes, Natalie Stone, the General Manager of CryptoPunks, would come by, slightly concerned, to ask if everything was okay and reassure us that it would be over soon. I kept assuring her not to worry. María Paula and I agreed that we were doing an okay job at our first big book signing, as we managed to write our names correctly upon request.

By the way, in 2011, I moved to Paris at the end of August for a year with a scholarship from the German Forum for Art History. For six months, I lived just a few meters from Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, which I strolled through almost daily during my walks in Paris when I wasn’t researching for my doctoral thesis at the German Forum for Art History. Anyone who has ever been to Parc des Buttes-Chaumont knows that it is one of the most beautiful parks in Paris. Not long before, I had finished my studies in Heidelberg and was suddenly living in a metropolis, or indeed, in a larger city for the first time. In 2011, Instagram was still relatively new. Photographers were either thrilled or not so thrilled by the then-called photo app, while I simply used Instagram as a social network to share what my life in the big city was like. Exciting. Of course. Photography was also a topic I was dealing with in my doctoral thesis, and so it happened that I began to engage with art and social media in Paris, and more broadly, with the history of digital art. Now, almost 15 years later, I found myself back in Parc des Buttes-Chaumont signing CryptoPunks books. An even bigger coincidence is that in two days, I have to submit an essay on the topic of AI and art, commissioned by the Max Weber Foundation for their magazine. For this text, I was supposed to discuss the upcoming exhibition on AI at Jeu de Paume with the director of the German Forum for Art History, Peter Geimer. All roads seem to lead back to Paris...

In March, an essay of mine will also be published, focusing on collectibles and the history of portraiture, which, of course, includes CryptoPunks. Here’s a very brief excerpt:

“With the CryptoPunks, the next chapter in the history of portraiture in art began. Since the 16th century, a portrait has primarily been a character study meant to express the essence of the person depicted. Even today, portraits are often commissioned works for artists. Matt Hall and John Watkinson provide portraits for the post-digital age: A choice can be made freely from 10,000 portraits.”

Meanwhile, international media are discussing the call for a boycott of the Christie’s AI auction, Augmented Intelligence. Should we expect that art itself will also be boycotted in the future? Isn’t the history of art a story of predecessors and successors?

By the way, a few weeks ago, I spoke with Avery Singer for the German art magazine Monopol about digital art and NFTs, which also included discussions about education at art schools. Avery Singer said:

“There needs to be a better connection between contemporary art and digital art, as there are people out there creating interesting works. However, I’m not quite sure how to establish that connection. Traditional artists are trained for four to six years, and curators often even longer. Digital artists, as I said, are often self-taught. (…) This creates two ideological frameworks that develop separately, without interaction. Interaction, however, should begin in these formative years. How can we integrate digital art into museums and art education?”

I believe the two separately existing ideological frameworks are the trigger for the current debate. It would be a good idea to look into which artists are in the auction and what their art is about. Among others, Mat Dryhurst & Holly Herndon, Kevin Abosch, Sougwen Chung, Sasha Stiles, and Harold Cohen are featured, along with two autonomous artists, Botto and Keke. Enough said at this point. Or as Mat Dryhurst shared in an Instagram story less than 24 hours ago: “Superficial engagement and attention economy wars in which no one reads about the subject material are a bigger threat to art and culture than diffusion models.”

Regarding Botto, Luba Elliott, Curator and Researcher, recently said in an interview with Verse: “Ultimately, Botto is an artist of multiple selves—the image-maker, the creative coder, the self-assessing critic—all running in parallel and destined to converge in the future as the evolved algorithms become seeds for prompt-based image works. Herald the Renaissance man for the agentic AI age.”

In 2021, Botto was created by the software collective ElevenYellow and the German artist Mario Klingemann. “Botto tries to cater to the taste of the majority,” says Klingemann. Botto learns what people like and orients itself to these judgments of taste when creating artworks. Does this sound both familiar and new at the same time? If I could, I would immediately head to London to attend the opening of Botto at SOLOS on February 18.

And lastly, something else I’ve been wanting to write a newsletter about for a long time but didn’t have the time to do so because this year has started very turbulently: I curated the exhibition The Second-Guess. Body Anxiety in the Age of AI together with Leah Schrager and Margaret Murphy.

The 10th anniversary of the influential online exhibition Body Anxiety, curated in 2015 by Leah Schrager and Jennifer Chan, serves as an occasion for Margaret Murphy, Leah Schrager, and me to explore body anxiety in the age of AI. In 2025, the exhibition looks back at the history of the relationship between humans and technology, as well as the beginnings of what is known as selfie feminism or networked feminism, and shows how the fight against censorship on social media has evolved into a fight against deepfakes in the age of AI. Once one's image is findable on the internet, questions of consent have again become relevant. The Second-Guess: Body Anxiety in the Age of AI features artists who questioned photographic truth at the time of the emergence of digital manipulation, who explore the relationship between humans and technology, identity, surveillance, and the use of media as a tool of empowerment against censorship and political repression since the 1970s, and who take a closer look at social relationships in the context of automation and algorithmic living.

“Whenever you put your body online, in some way you are in conversation with porn…” With these words, American artist Ann Hirsch welcomed visitors to the Body Anxiety exhibition in 2015. Ten years later, Ann Hirsch says that she would watch more TikTok. Ten years later, however, a new generation of artists has also emerged. With the rise of new technologies such as blockchain and AI, the history of digital art since its beginnings in the 1950s is being increasingly re-examined. More than 40 artists in the exhibition were born between 1941 and 2000. In 1941, civil engineer Konrad Zuse completed the construction of the Z3 in Berlin, the world's first functioning programmable, fully automatic digital computer. The year 2000 is often referred to as the year of the "dot-com boom." Generation Z thus grew up in a world where digital media were ubiquitous, and the boundaries between physical and digital reality increasingly blurred.

Body Anxiety shared the varied perspectives of artists who examined gendered embodiment, performance, and self-representation on the internet. Social media platforms like Tumblr and Instagram were the places where artists showcased themselves, exchanged ideas, and shared their artworks. It was an era dominated by women artists who could finally own their image but had to fight against censorship. There was a lot of excitement when artists began sharing photos of themselves on social media. Arvida Byström, Molly Soda, and Leah Schrager, for example, depicted themselves as feminine, sexy, and sad. Lost in thought, they gazed into their smartphones, mirrors, or the eyes of the viewer. There was pink everywhere, hair on their legs and underarms, and blood in granny panties.

The exhibition was presented on a website in 2015. In 2025, the exhibition is showcased in a metaverse (HeK Basel), on Substack (beginning of March), and on an NFT platform (objkt.com on Tezos, starting at the end of February). Visit the exhibition here.

Thank you!

Love,

Anika

P.S. I highly recommend watching the series Severance. My favorite scene so far:

"I understand that you are unhappy with the life that you've been given. But you know what? Eventually, we all have to accept reality. So, here it is. I am a person. You are not. I make the decisions. You do not." – Helly R.

The persistent gap between ‘traditional’ and ‘digital’ arts is a continuous source of frustration of many artists/educators that have been trained in a ‘traditional’ art context, but moved to integrate digital technologies in their bodies of works over the course of the last decades. Indeed; we feel ‘self taught’ in understanding our mediums, but at the same time we come from rich feeding grounds that recognise experiments in recent (and less recent) art history.

It seems that the ‘traditional’ arts approach technologically-assisted arts from a one-sided view: it is constantly associated with a dystopian view on technology, a suspicion and concern towards big data and military applications and so forth that is shared by most (if not all) digital artists. This causes a lack of understanding the medium and the motivations of the artists for working with and around these technologies: this seeps on to curators and collectors, who have no idea how ‘read’ digital art (unless it is output as ‘traditional’ art, such as 3d or 2d prints).

On the other hand, and I speak from my own experience, the sometimes rather hostile attitude towards artists who are engaging intensively with digital media forces us into the defence, which is just not a very pleasant place to be – avoiding the ‘traditional’ art world is one way to escape that, but at the same time keeps the gap open.

It makes me a bit wary for young artists, who – unlike my generation – grow up with a more integrated view on technology; students who are interested in using digital media as artistic tools are almost just as much on their own as I was (at least here, in Belgium, where there is only one department of ‘new media’ in a School of Arts; all other education is aimed at applied goals, games, commercials, etc).

Perhaps we should organise a Summer School, Anika!