AI Art Questionnaire: Kevin Abosch

10 Questions on AI and Art to Explore the Intersection of Creativity and Technology

This is the second interview in the form of a questionnaire in a series of conversations about AI and art. The beginning was made by Senegalese artist Linda Dounia, who was recognized in 2023 on the TIME AI 100 list of the most influential people in AI for her work on speculative archiving. The Irish conceptual artist Kevin Abosch challenges conventional notions of value and identity. He sold a photograph of a potato for $1 million in 2016, worked with Ai Weiwei on “Priceless” (2018), tokenized shared moments between the two on the Ethereum blockchain, tokenized himself on the Ethereum blockchain in the form of 10 million works of art, and sold a neon sculpture he made of a blockchain address that symbolized Lamborghinis for more than the price of a real Lamborghini. “The meta-weirdness around the purchase of the art is at the heart of the questions Mr. Abosch wants to explore,” wrote The New York Times in 2018. With “AM I?”, he just premiered the first fully AI film made by a single person at the Helsinki International Film Festival.

Anika Meier: When did you first learn about AI?

Kevin Abosch: In 1992, just four years after first identifying as an artist, I found myself up to my neck in machine learning. We didn't really call it “AI” back then. We talked about neural nets and “fuzzy logic.” I had learned that the false negative rates in laboratories analyzing Pap-smears, the test for detecting cervical cancer and human papilloma virus (HPV), was alarmingly high. It wasn't so easy for human lab technicians to eyeball a Pap-smear slide under a microscope, and definitively determine whether a given sample was abnormal or not. I wondered if a computer trained on a large set of morphological data from many thousands of Pap tests, couldn't produce more accurate results, which was literally a matter of life and death.

I spent months poring over academic papers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and CalTech. With a bit of support from Steve Jobs and NeXT computers, the company he founded after leaving Apple, I spent two years developing an automated Pap test analysis system leveraging conventional microscopy, nascent computer vision technology, and, yes, fuzzy logic.

The devastating Northridge earthquake of 1994 thwarted my work, as the building that stored 150,000 slides that were to serve as my dataset, was destroyed. Fortunately, others eventually built what I had envisioned. With all this acquired experience working with computer vision and early AI, I had found a new set of tools that intrigued me as an artist.

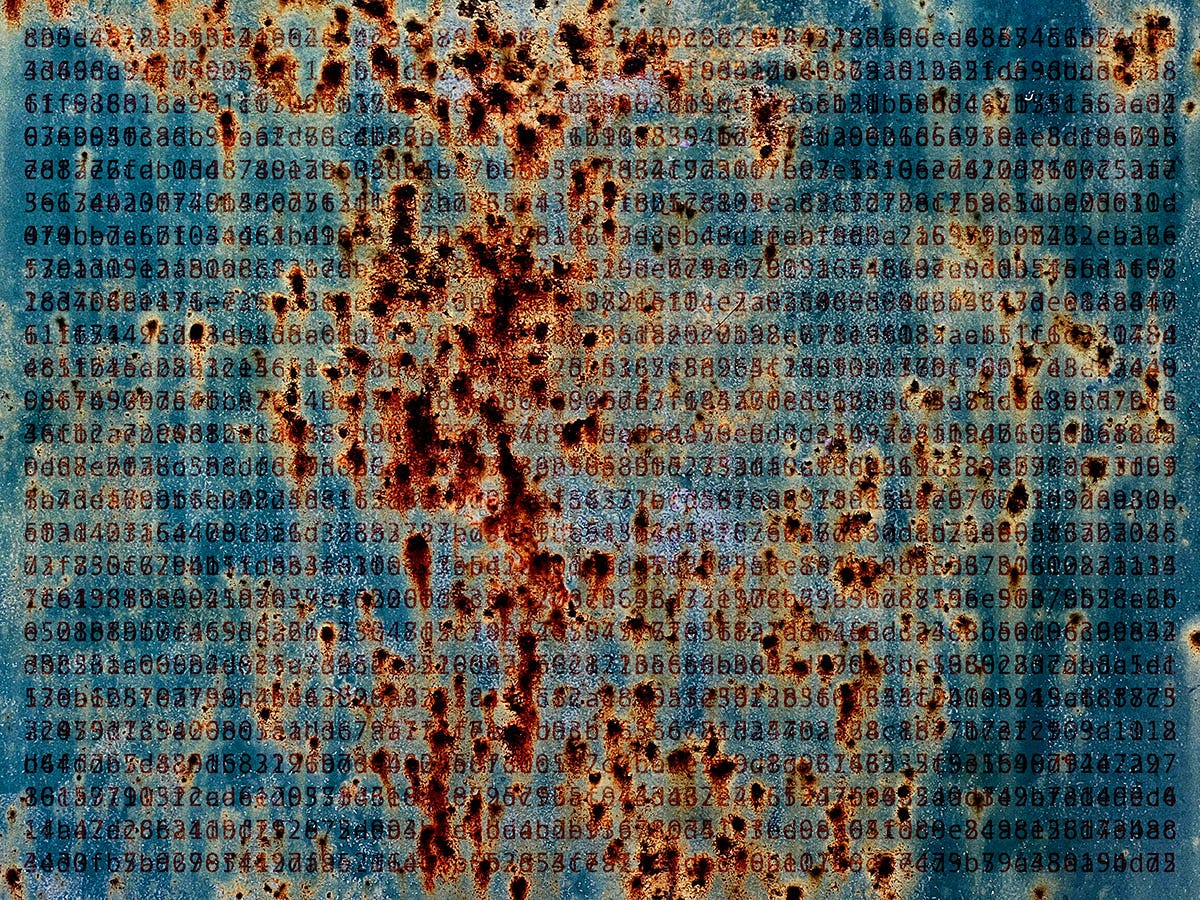

I programmed expert systems which applied rule-based logic to a knowledge-bank of daily-updated public datasets like weather, financial markets, even Hollywood box-office numbers. Based on a complicated set of if/then statements in the code, the computer would output a set of instructions related to the construction of an artwork. These were not data visualizations. I used the data to inform the process rather than treating it as the subject of representation. This method uses the data as a dynamic, generative component in the artistic process, making the art an ongoing dialogue or interaction with the data sources, rather than a static depiction of them.

It has been said that I treat photography similarly. The subject is not merely captured; it is interpreted and transformed, turning each photograph into a narrative that extends far beyond the visual representation.

AM: What did you think about AI back then?

KA: I've always thought of AI as a tool that could serve to extend our senses and skills. At its best I thought it could make us superhuman. I'm from the first generation of children with computers in the home. In the summer of 1981 while visiting my family in Ireland, I convinced my mother to buy me a Sinclair ZX81 computer kit, which had a whopping 1KB of RAM and ran a simplified form of BASIC. My only other hands-on experience with a personal computer had been on a Tandy TRS80 at school. Over the next few years, computers would come and go. Using money I would make from buying old bicycles, fixing them up and selling them for a profit, I bought a Sanyo MBC550, an MS-DOS machine, followed by a TeleVideo TS-802 which ran both CP/M and TeleDos, and had enormous 8-inch floppy drives. My friend's father had a modem, and we would get into all sorts of trouble, accessing company mainframes and poking around where we weren't supposed to.

I would spend countless hours at thrift stores in Los Angeles finding college-level textbooks that I could purchase for as little as 25 cents. My library consisted of books ranging from thermodynamics and molecular biology to topology and early computer languages. By the age of 12, I was proficient in Fortran and COBOL. The machine had become a significant presence in my life. I mean, it was in my bedroom. So what did we do with our computers? You could visit bulletin boards (BBS) and acquire knowledge that you just couldn't find elsewhere... hacker stuff. We coded crude games and when color monitors came out, it really felt like the computer had become more playful, and most importantly, a place where artistic expression had gained 256 colors to play with. You could make pretty graphics. You could make interesting graphics. Maybe one day you would make something meaningful.

AM: Has your opinion about AI changed?

KA: I still marvel at how, when used cleverly, AI can help surface data that we would most likely never become aware of without it. Once you see something through the “eyes” of the machine, you are forever changed. Under the influence of the machine, we dance with transhumanism. Perhaps today, I am a bit more concerned about what happens if one begins to lose their humanity by onboarding too much AI. It's a theme I explore regularly. People speak of the necessity of “touching grass” as a counterbalance to the burden of our tech-laden lives. It's essential.

Because of my work with AI, I get brought into discussions amongst corporate and governmental leadership, keen to weigh the upside against the downside of this emergent technology. From matters of data privacy and the weaponization of data, to the ethics and legality of the data used in training models, the discussions usually become quite heated, one way or another. The most animated and vociferous of participants seem to be in a state of fear. Whether it's fear of being replaced, fear of losing money, or fear of the unknown, I firmly believe that fear subverts logic, which makes having a rational discussion about AI most challenging. We came into this world, surrounded by a cinematic and literary legacy that assured us of one thing... that one day, it will happen... the machines will take over, and it will be devastating for humanity. So, unless we can short-circuit what has in a sense been programmed into us collectively, we will continue to live in fear.

In my practice as an artist, I challenge conventional notions of value and identity, which can be unsettling for many. We find comfort in stability, so when it is suggested that the concepts, traditions and “truths” we view as settled become unsettled, fear can creep in.

Take my photographic work “Potato #345” (2010) for example. It challenges the notion that we as humans are superior in every way to the lowly tuber. Spend time with the work, especially in person with the 1-meter square print, and one starts to feel small. You see yourself in the image. You feel like a child, which is both exhilarating and potentially terrifying.

When I tokenized myself on the Ethereum blockchain (“I AM A COIN” (2018)), in the form of 10 million works of art, intangible ERC-20 crypto-tokens, many refused to accept that something they could neither see nor hang on their wall could have value. Their value system was challenged. Ironically, some of the same people who made this argument were investors in Bitcoin, an intangible asset.

With my early synthetic photography using GAN and diffusion algorithms, there were plenty who panicked. Comments included, “What you’re doing is undermining the value of real photography!” and “What you’re doing is unethical!” Of course, what many failed to notice was that the models I was using in 2017/2018 were trained entirely on my own artwork. Later works, which would also include data from public AI models, would be attacked by some as “collaging the work of other artists,” which is a statement borne out of ignorance. A bit of education about how the technology works and much of the fear would be neutralized.

My point is, the artist is in some ways fighting a proxy war that illuminates some of the most polarizing issues of our time. New headlines designed to get clicks make matters worse. So many aspects of our lives are already being manipulated by the algorithm. The question we need to ask repeatedly is who controls the algorithm, and what are we going to do about it?

AM: What's your favorite book about AI?

KA: “Neuromancer” by William Gibson is the first that comes to mind. I appreciate how it presents AI in a way that transcends the usual humanoid form, like in Asimov's “I, Robot,” another great book. Focusing instead on the complexities of consciousness, autonomy, and the merging of technology and human experience. Despite my ambivalence about humanoid AI, the novel's portrayal of artificial intelligence as a disembodied, pervasive force within cyberspace resonated with me. It explores the possibilities of AI beyond the physical, inviting reflection on how technology and data manipulation can radically reshape society, identity, and control. Disrupting human agency taps into my own artistic concerns about AI.

Many of my peers assume I am a fan of science fiction, and while this may be true today, it wasn't always the case. When I was younger, while entranced by the portrayal of what science could look like in the future, I was far more into non-fiction, and specifically books about the science of our time.

AM: Who is your favorite thinker on AI?

KA: Marvin Minsky, one of the founders of the AI lab at MIT, was someone I had the invaluable opportunity to spend time with. He had a huge influence on how I view this thing we call AI by shaping my understanding of AI as a tool rather than something to be feared or mystified. His perspective on artificial intelligence was grounded in the idea that it could extend human capability, acting as an amplifier of our intellectual reach rather than a replacement. Through our conversations, I came to see AI not as an independent force, but as something we could mold and harness, a tool that could augment our creative and problem-solving processes.

AM: How did you get started working with AI as an artist?

KA: In working with a camera, I have always sought to understand the boundaries, if and when they exist, between myself as a photographer and my subjects. Where do I end and where do they begin, and vice versa? The same can be asked about the relationship between the artist and AI. As I said, in working with AI in a practical sense with respect to cytology in a laboratory setting, it was impossible to avoid thinking, as an artist, how could I extend my abilities? Of course today the work is as much about the impact of AI on society as it is a tool towards an end.

AM: What is your first AI artwork?

KA: My first AI artwork was executed in January 1994 in Los Angeles and entailed a “gravid sac” that I formed by placing a polystyrene ball inside a polyethylene bag and tying the top to a horizontal metal rod so it could hang freely. Using the programming language LISP, I created an expert system that took the daily closing value of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the price of a barrel of crude oil, and a random number chosen by my father, and applied a series of complicated rules, generating a numerical value corresponding to a quantity for which I would add a white acrylic medium to the work with a toothbrush.

Even back then, I chose to use machine learning in seemingly impractical ways. On January 31, 1994, the work was completed. My friend Henry Geldzahler saw the work and asked me what the title of the work was, and I said it was yet untitled. He said, “Good,” so I left it like that.

AM: What is your most recent AI artwork?

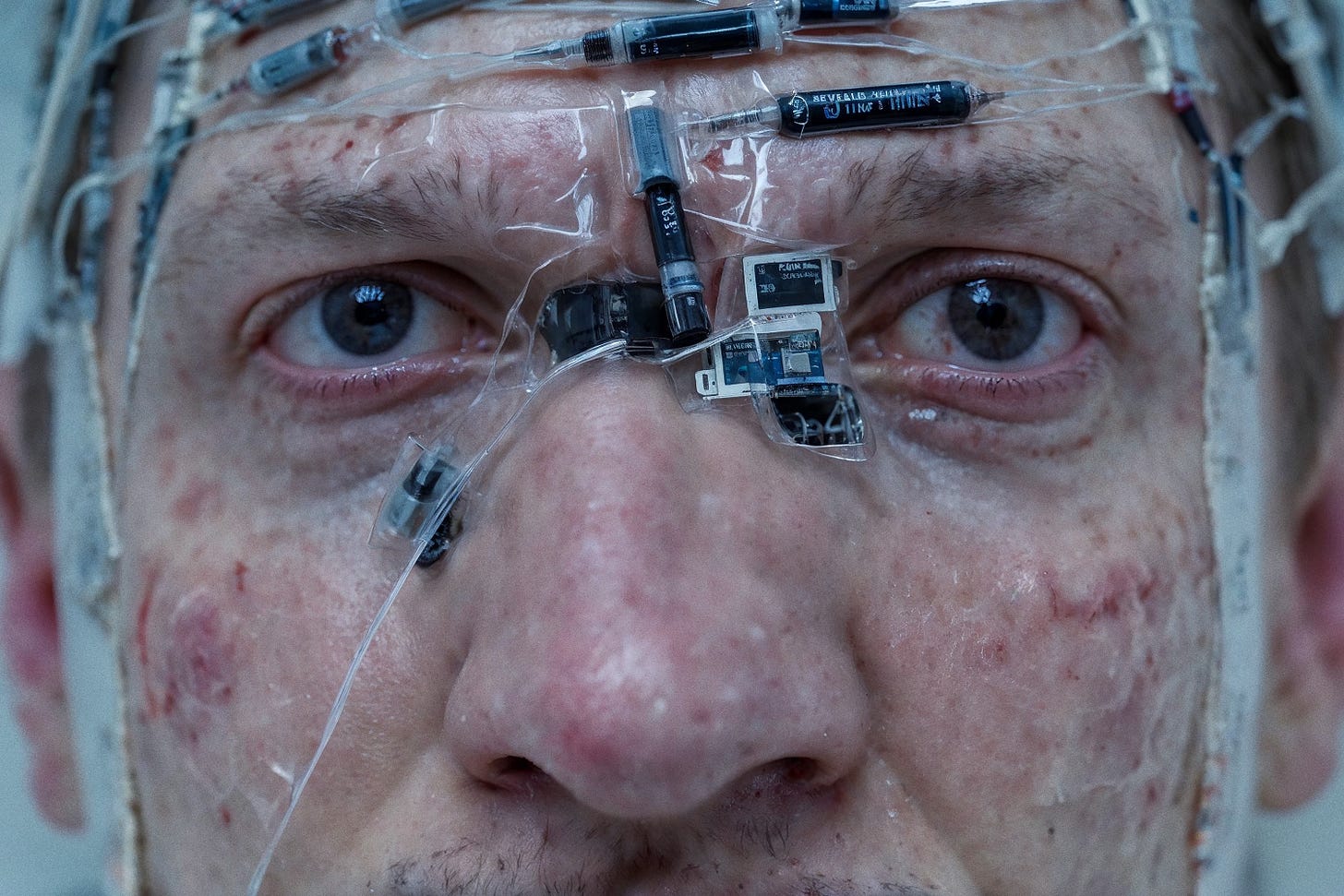

KA: My most recent AI work is a feature film, every frame of which is synthetic. It’s called “Am I?” and is a musical embedded in a documentary, wrapped in a sci-fi film. Guided by the voice of an AI, the audience is thrust into a stream of content and narrative around the possibility of losing our humanity by allowing ourselves to be consumed by technology.

It recently had its film festival premiere at the Helsinki International Film Festival and was quite well received. I posit in the film that by inviting technology into our lives and relying on it to manage aspects of our lives that we traditionally took care of ourselves, we move squarely into the realm of transhumanism.

As the first fully AI film made by a single person, “Am I?” has put me in the crosshairs of some in Hollywood concerned about AI replacing talent of all types with the machine. The fact is that this is a film that only exists because I made it using AI. I would never have made this film in the conventional way. At the same time, the interest from Hollywood has been much greater than I imagined. At the screening in Helsinki, during the Q&A afterwards, an audience member took the microphone and declared, “We have witnessed the birth of a new cinema!” The audience applauded. Indeed, I think those of us who are interested in how AI will play a role in the production of movies are not thinking about how to replace talent. We are thinking about novel ways to tell stories and to entertain. All the AI in the world won’t help the filmmaker, who doesn’t know what an honest moment feels like.

AM: What do you dislike about the current conversation regarding AI and art?

KA: I don’t like when the “AI” comes before the art. AI is a tool for me, first and foremost. It’s also a thematic element in much of my work. Today, there seems to be a lot of enthusiasm for AI in art, and I suppose because many of those using machine learning in art-making have backgrounds in technology rather than in art, we see a lot of posturing and jockeying for some imaginary position. There’s a lot of “but I did that first!” and sometimes it’s just embarrassing. I often wonder if some of the “artists” I meet aren’t trying to win a Nobel Prize! So, to answer your question succinctly... I dislike everything that gets in the way of the art itself.

AM: Who are your favorite AI artists?

KA: I’m afraid I don’t have an answer to that question, but I have a collection of many thousands of artworks, including more than 5000 works of generative art, including those made using various flavors of AI. When it comes to AI, my preference is for synthetic photography. When you understand a medium, perhaps it makes it easier to identify works of great significance.

My art collection includes works of photography, modern and contemporary paintings and sculptures, generative and computer art, and outsider art. The artists in my collection off the top of my head include Man Ray, Alberto Giacometti, Jean Tinguely, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Nam June Paik, and Mike Kelly. You asked about AI, so some of the artists I’ve collected in the NFT and post-NFT eras are Robbie Barrat, Memo Akten, Sofia Crespo, and Mario Klingemann. This is a horrible question. Alkan Avcıoğlu, Katie Morris, Frank Manzano. I’ve collected the works of dozens of artists. I’ve even collected your AI work. This isn’t fair! Bård Ionson, Albertine Meunier, Ganbrood... I have to put the kids to bed.

BIO

Kevin Abosch (born 1969) is an Irish conceptual artist who works across traditional mediums as well as with generative methods, including machine learning and blockchain technology. Abosch's work addresses the nature of identity and value by posing ontological questions and responding to sociological dilemmas. His work has been exhibited worldwide, often in civic spaces, including The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, The National Museum of China, The National Gallery of Ireland, Jeu de Paume in Paris, The Irish Museum of Modern Art, The Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina, The Bogotá Museum of Modern Art, ZKM Karlsruhe, and Dublin Airport.